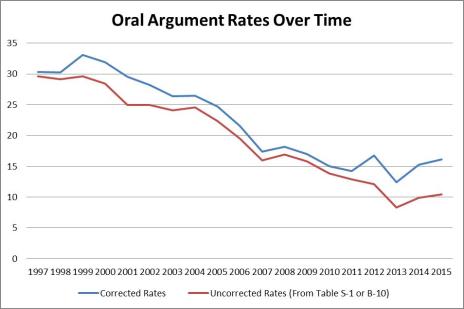

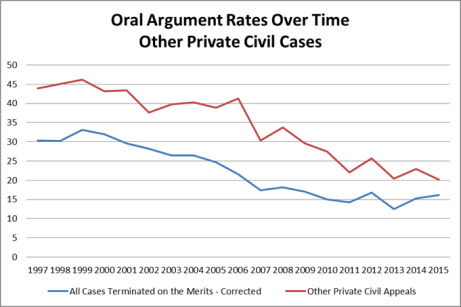

In my last post, I showed that even with corrections to remove the effects of changes in how the Administrative Office defines cases terminated on the merits, the Third Circuit’s oral argument rates have been generally declining over the FY 1997 to FY 2015 period:

Graph 1:

Based on available literature, this decline is not a new phenomenon and it’s not limited to the Third Circuit. See, e.g., David R. Cleveland & Steven Wisotsky, The Decline of Oral Argument in the Federal Courts of Appeals: A Modest Proposal for Reform, 13 J. App. Prac. & Process 119, 142 (2012) (commenting on declines since the 1980s). But putting aside the effects of case processing procedures that serve to enhance efficiency and other such forces, what’s contributed to the continuing downward trend?

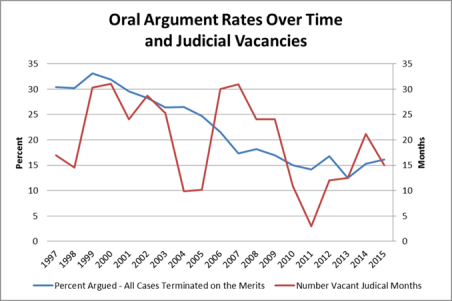

First Posited Reason: Judicial Vacancies

Some have speculated that judicial vacancies explain the decline in the Third Circuit’s oral argument rates – particularly in recent years. I don’t doubt that multiple vacancies that remain unfilled for several years can affect a judge’s decision to request oral argument in cases that are borderline. But I don’t see that judicial vacancies can fully explain the blue line above.

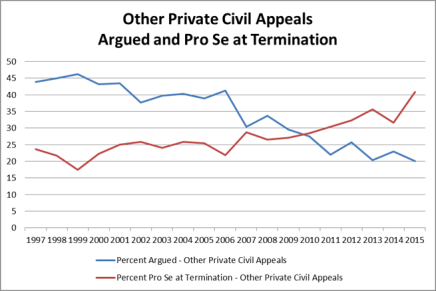

Graph 2:

Graph 2 shows judicial vacancy months (red line) along with the corrected oral argument rates over time (blue line). The Third Circuit has experienced multiple fiscal years with 24 or more vacant judicial months (the equivalent of at least two vacancies for the entire fiscal year). Between FY 1999 and FY 2003 and again between FY 2006 and FY 2009, the number of vacant judicial months ranged from 24 to 31. But oral argument rates have declined fairly steadily from about FY 1999 to about FY 2011, when they level off. If judicial vacancies explained oral argument rates, those rates should both fall with increases in vacant judicial months and rise with decreases. The graph above doesn’t reflect that – there’s no “uptick” in oral argument rates when the number of vacant judicial months drops. Even if vacancies have had some effect, they are not the whole story.

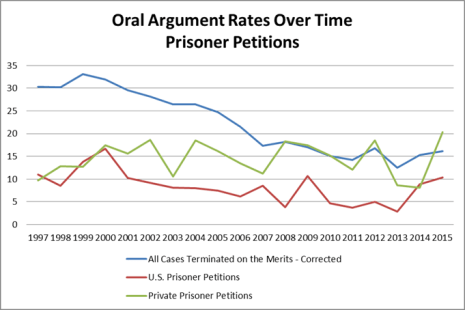

Second Posited Reason: Pro Se Cases

Another possible reason for the declines in the oral argument rate (and the publication rate – another focus of recent attention) is the increase in the number of pro se cases now being litigated in the courts of appeal. The Administrative Office’s statistics suggest that in FY 2015, just over 60% of all cases the Third Circuit terminated (both merit and procedural terminations) were pro se at the time of termination. That’s a huge percentage, and much larger than it was in the late 1990s. It would make sense that pro se cases are less likely to be argued.

Pro Se Prisoner Petitions

Prisoner petitions are by far the most likely cases to be filed and prosecuted pro se. Based on the Administrative Office’s statistics for the FY 1997 to FY 2015 period, the percentage of prisoner appeals that were prosecuted pro se was fairly constant: an average of 84% of U.S. prisoner petition appeals were pro se at termination, with a low of 76.4% (FY 2004) and a high of 90.1% (FY 2011). An average of 88% of private prisoner petition appeals were pro se at termination, with a low of 83.6% (FY 2004) and a high of 93.5% (FY 2013). If pro se prisoner petitions (1) are less likely to be orally argued and (2) made up an increasing percentage of the Third Circuit’s case load, then the combination could explain the declining oral argument rates over time.

But, over the FY 1999 to FY 2015 period, the percentage of all the Third Circuit’s cases terminated on the merits that were prisoner appeals was also fairly constant, averaging just under 19%. In the midst of the period of declining oral argument rates, the percentage of prisoner petitions also declined, going from a high of 23.8% (in FY 2003) to a low of 13.7% (in FY 2010). For that period, at least, prisoner petitions were making up a smaller – not larger – percentage of the cases that the Third Circuit terminated on the merits.

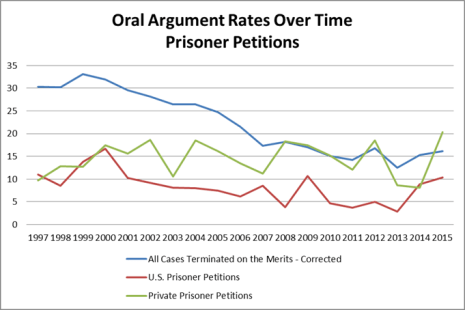

The relative steadiness of prisoner appeals as a percentage of all cases terminated on the merits and of pro se prisoner appeals may be why oral argument rates for prisoner petitions don’t show the same downward trend that all cases do:

Graph 3:

Pro se prisoner appeals do not appear to be the explanation for declining oral argument rates over time.

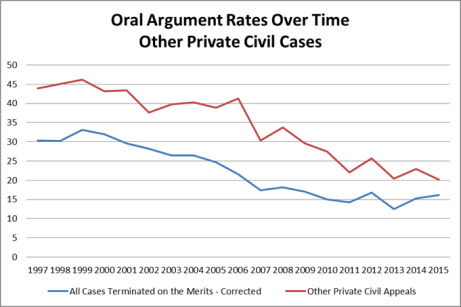

Other Private Civil Appeals

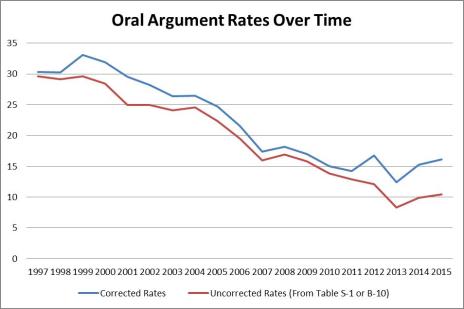

Where an increase in pro se cases may have a substantial effect on oral arguments rates is in the category of other private civil appeals (a category that includes every civil appeal that is not a prisoner petition or a bankruptcy appeal). Oral argument rates for such appeals show the same downward trend as the overall rate does, although the decline is sharpest after around FY 2006:

Graph 4:

Between FY 1997 and FY 2006, the Third Circuit heard argument in an average of just under 42% of cases falling into the “other private civil appeals” category. The oral argument rate dropped dramatically after FY 2006: between FY 2007 and FY 2015, the average rate was 25.79%. So what happened after FY 2006?

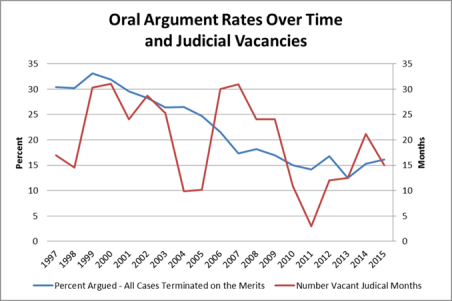

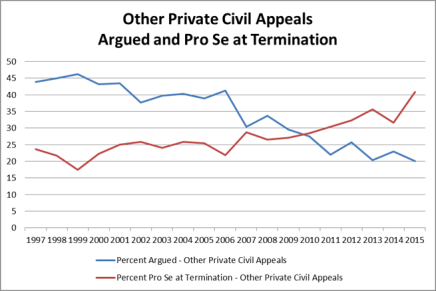

Graph 5:

Before FY 2006, the percent of other civil cases that were pro se at termination was, at its highest, just over 25%. After FY 2006, the smallest percent pro se at termination was over 26% and averaged about 31%. And, as Graph 5 shows – pretty dramatically – as the percent pro se goes up the oral argument rate generally goes down and as the percent pro se goes down the oral argument rate generally goes up.

Bottom line: the increase in the percentage of other private civil appeals that were prosecuted pro se may be a reason for the declining oral argument rates over time.

The other private civil appeals category is not the only one for which the percent pro se at termination has increased. A much larger percentage of criminal appeals were pro se at termination starting in FY 2009. The percentage of agency appeals that were pro se at termination jumped for a brief period between FY 2000 and FY 2002. Another jump in the percent pro se began in FY 2012. Why are more cases being prosecuted pro se?

This leads me to show one more graph:

Graph 6:

Attorney salaries were increasing over the 1998 to 2010 period, after which they leveled off. As I mentioned above, oral argument rates in the Third Circuit have declined fairly steadily from about FY 1999 to about FY 2011, when they level off.

Coincidence?